Building the future

To build the future, we must learn from history

When asked to present on the arguments for shifting power out of Westminster, I usually start with two pictures.

Sources: West Yorkshire Archive Service and Mike Knapton/Wikipedia

Managed to guess where they are?

The first is a tram system in Huddersfield. The second is the Haweswater reservoir in the Lake District.

But why these two pictures?

Because they were both built by local government.

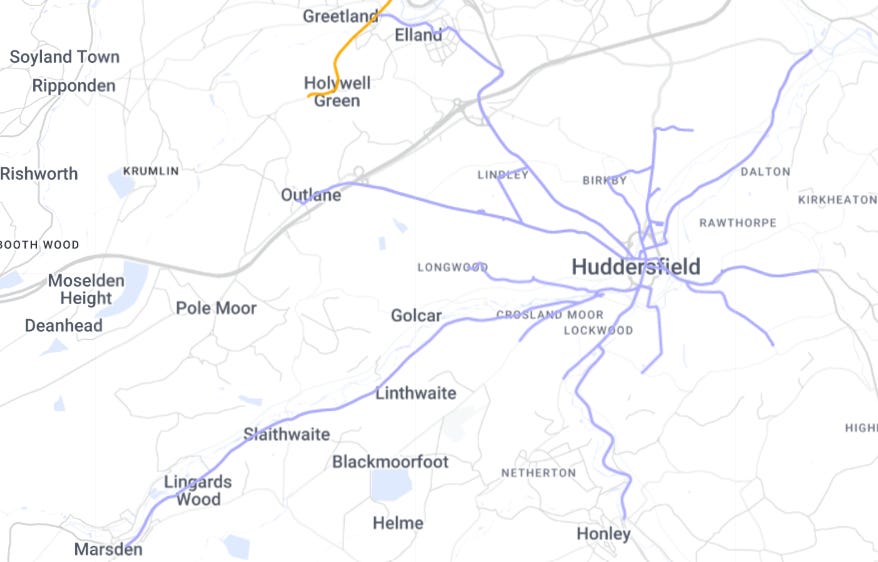

The Huddersfield tram was built in the 1880s. It became the first one to be municipally operated - requiring an additional Act of Parliament to be passed. Trams ran to at least a dozen destinations by the 1930s. The extent of the network is shown in the image below. The similarly extensive Halifax tram network pokes down from the North to meet it.

Source: Rail Map Online and Google Maps

The Haweswater reservoir was built to supply water for the residents and businesses of Manchester, as was nearby Thirlmere. Thirlmere was built around the same time as the Huddersfield tram system started in the 1880s and Haweswater was constructed in the 1930s. These also required Acts of Parliament to enable construction. 1

Imagine a world in which local government in the North (and elsewhere) just builds things, solving problems for its residents. This is the world we used to live in.

We’re now one of the most centralised countries in the developed world. And this has been bad for the whole country for two reasons:

It means we simply get less stuff done as everything has to run through the centre more than it used to do.

It has led to a consistent bias of different types of spending towards different parts of the country - leading to a system that doesn’t really work for anywhere.

I’ll look at each of these issues in turn.

Firstly, let’s look at the extent of centralisation.

The chart below shows that we have the most centralised tax and spend decisions in the G7. Just 6% of tax revenue is controlled subnationally, compared to an OECD average of 30%.

We went from a position where local government raised at least 70% of its own income before 1950, to one where this had reduced to about 40% by 2001.2

This share has increased again in recent years, mainly driven by cuts to central government grants. But in reality this has forced councils to rely on increases in Council Tax to make up some of the difference, a tax which itself is heavily controlled by central government.

That is why the cross-party commitment towards devolution of power is so welcome. A process begun by New Labour, built upon by Conservative governments and pushed further again by Labour in office.

The English Devolution and Community Empowerment Bill now before parliament will formalise a new tier of strategic authorities and mayors across the country. The Bill includes a clear bias towards further devolution.

There is a ‘right to request’ provision meaning mayoral requests for new powers must receive a response from ministers, as well as a clause requiring parliamentary approval if any powers are to be recentralised. It will also allow mayors outside London to effectively appoint a cabinet of deputies for the first time. And it defines mayoral powers very broadly including a ‘general power of competence’ and areas of responsibility ranging from transport and housing to public service reform and public safety.

But this has to be just the start. For a country of our size and stature, it does not make sense that the national government and the national parliament are so involved in issues like building local tram systems, connecting local colleges with local businesses or even pothole maintenance.

National government should be an enabler, but it is simply too remote and too important to be spending much time on local issues compared with the challenges of the macroeconomy, major national project delivery or foreign policy in the current age. When you consider the opportunity cost, we should be honest that any moment someone like the Prime Minister or Chancellor has to spend worrying about potholes is time wasted.

Fortunately, we are seeing a renaissance in a more local way of thinking. For example, Greater Manchester is developing an integrated transport system which is the most advanced outside London. The most recent line built - the Trafford Park line - was opened in 2020 and came in ahead of time and on budget.

More local delivery requires strategic and local authorities to have the power to control their own income. Some of this might be through charging for services, like trams and buses, but some of it will be through tax revenue.

This does not necessarily mean increasing taxes, but it does mean local government having control over revenue rather than almost everything being controlled by central government. Calls for a tourism tax by mayors are one part of this - but there will be a need to go even further - if we are to change our position in the chart above.

Secondly, it is sadly evident that centralised decision making has favoured spending in some parts of the country over others.

In a report for Labour Together, I set out how government spending on growing the economy (so on areas like transport, research and education - what I call ‘growth spending’) was consistently higher in the Greater South East of England than in the rest of the country.

If we just look at the North, we can see that an average of £2,986 per person was spent on growing the economy in 2023-24. This compares within £3,585 in the Greater South East. A 17% gap.

The difference is more pronounced in certain policy areas. For example, the gap is 39% on science and technology spend (£175 v £106 per person) or 29% on transport spend (£867 v £615 per person).

On the other hand, spending on ‘social protection’ (i.e. welfare payments) is much higher in the North versus the Greater South East (£5,452 v £4,816) and public spending as a whole is slightly higher in the North (£12,956 v £12,804). Without the fiscal transfers from the South East this would not be possible (see ONS data).

The per person numbers may sound small but, when totalled up across society and over the years, they amount to tens of billions (see further detail in the report). These are the statistical symbols of an unbalanced society.

Not only do we need to devolve decision making if we are going to get more done, but we also need to fundamentally change these spending patterns if we’re going to create a thriving North.

The government has made a good start on redressing this including the commitment to the £15.6bn Transport for City Regions fund announced in June and the Devolution Bill mentioned above. But more will be needed if we’re going to allow places to deliver for themselves.

News reports are promising in this regard. The Times has said that the Chancellor is looking to address ‘regional inequality’ and put ‘new life into George Osborne’s Northern Powerhouse’. The Yorkshire Post and the Guardian have recently reported that Northern Powerhouse Rail will be confirmed before or during conference season. The North has been here before, so delivery is essential.

The green shoots are already there in Greater Manchester, the fastest growing part of the country over the past decade.3 An exciting sign of progress that I’ll return to in a future post so we can try to understand what is going on.

With more local control over decision making supported by a more equitable spread of resources we should see a sustained resurgence of prosperity across the North.

Tram plans are already in the works in many places. When it comes to reservoirs, some might say that it is too much to ask for places to start building them again. But then again - why not?

If you’ve found this post interesting - or think others will - then please share or subscribe if you haven’t already.

And if you have any feedback or suggestions for future topics just hit reply or let me know in the comments.

As an aside, you might think it's impossible to shoehorn in a reference to Oasis here. But you’d be wrong. The aqueduct bringing the water down from the Lake District connects to Heaton Park Reservoir in North Manchester. Yes, the same Heaton Park that hosted the recent Oasis gigs.

Just to repeat - Greater Manchester was the fastest growing part of the country in the past decade. So understanding why this is the case should be central to our growth story. My suspicion would be some combination of devolution and extra investment. Sadly the figures on spending by policy area aren’t split out at a lower level than regions.

Land value taxation is part of the answer. LVT should be a purely local tax, giving LAs the responsibility and incentive to manage the land in their jurisdiction to increase its value and hence their tax receipts. And they should be able to use it to guarantee the coupon on bonds they would issue (escaping Treasury underwriting constraints). These bonds would be ideal to finance infrastructure, which increases the value of land affected by it, and hence would increase the return on/value of bonds to investors.

https://departmentofmisplacedideas.substack.com/p/kill-all-dogs-and-other-reasons-democracy