Let Tracy Build

Mayors should be allowed to just build transport projects

“Let Mayors Build” published today makes a simple argument: we should allow mayors to be the builders of great transport projects, rather than forcing them to act as campaigners.1

And given we nearly have 100% coverage of mayors in the North, I think the benefits of such a change would be huge here.

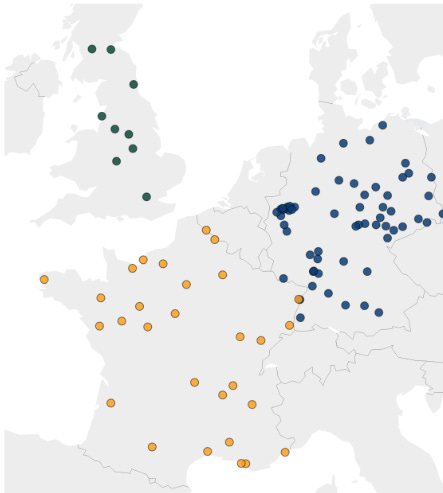

Every French city with a population greater than 150,000 has some form of mass transit system. Germany has a huge coverage of such networks as shown in the map below (taken from the report).

Map: Tram and metro coverage for France, Germany and the UK

Replicated here in the North, this could mean places like Leeds, Bradford, Hull, Huddersfield, Bolton, Warrington, York, Preston, Middlesborough and more all being connected to mass transit systems over the coming years.2

Infamously, Leeds remains the largest city in Europe without a mass transit system. And as Tracy Brabin says in the foreword to the report: ‘this is wasting potential - not just for Leeds and the rest of West Yorkshire, but the whole country.’

At the moment, mayors are forced to campaign for funding and powers to deliver trams and other infrastructure in their own areas. Even the very welcome ‘Transport for City Regions’ funding still relies on waiting for central government to confirm funding totals and any projects worth over £200m will be subject to a centrally approved business case.

This brings most mass transit projects within the scope of central control, despite the devolution of funding. For example, the successful 2020 completion of the Trafford Park line in Greater Manchester cost around £350m - before taking inflation into account.

Taking forward the recommendations in our paper would give mayors the ability to fund and approve more transport projects.

In terms of approvals, mayors should be able to grant their own Transport and Work Act Orders to get on with building. They should also not be required to get central approval for transport projects valued over £200m, where the projects can be funded from within integrated settlements or from the mayors’ own funds.3 Where projects still require central approval or funds, an expedited approvals process should be followed to speed things up.

In terms of funding, mayors should be able to use the tools available to previous mass transit schemes such as business rates supplements and workplace parking levies, without the need for central approval or enforced requirements. As well as a tourism levy, a targeted council tax precept around new stations could also be considered.

Together, these changes would speed up and cut the costs of transport projects. Data shows that underground lines cost just one sixth per mile in Spain compared to Britain. And French trams are half as expensive as British ones.4 Where local areas are responsible for delivering, they have a clear incentive to keep an eye on costs - just like the on-budget and ahead of schedule Trafford Park scheme mentioned above.

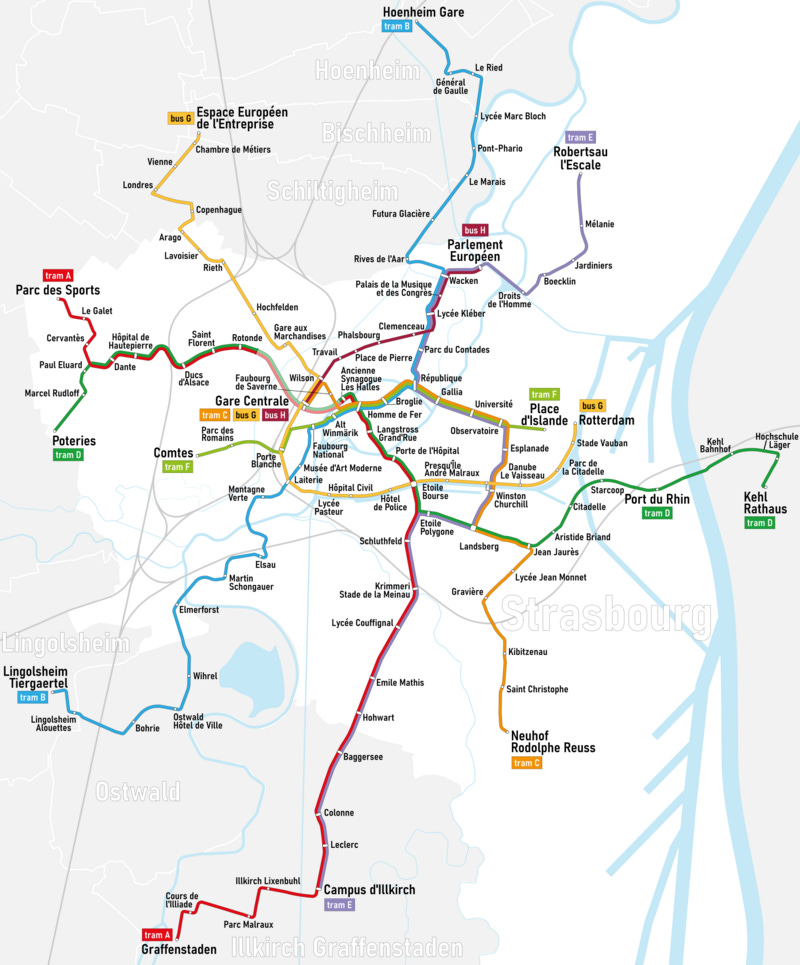

The report cites the example of Strasbourg, a city of around 300,000 in a wider area of 800,000 people in eastern France. In 1989, Catherine Trautmann was elected as mayor on a promise to build a tramway, a pledge fulfilled with the opening of the first line in 1994 - just five years later. In 1995, Trautmann won re-election - and Strasbourg now has an extensive transit network as shown below.5

Source: Wikipedia, Maximilian Dörrbecker

If we lived in a country where our mayors had the same powers to get on with stuff like the French, Tracy Brabin - elected for the first time in 2021 - and the people of West Yorkshire could have been looking forward to the ribbon cutting of the new tram next year.

Instead, given the central restrictions put on areas over decades, we’ll be looking to see construction starting by 2028 - two years later than Strasbourg took to actually build a line.

With the right powers and funding for mayors, building trams like we used to - and catching up with the French and Germans - can be achieved in the coming years. Now let’s get on with it.

Full report available here. This report has been the result of a collaboration between Labour Together and the Centre for British Progress, with myself, David Lawrence and Ben Hopkinson as co-authors.

This is not meant to be an exhaustive list. And data on the population size of urban areas is a notorious minefield given definitions. So depending on how you count 150,000 population, this could also be extended to include other places - particularly in the hinterlands of existing or planned networks - such as Barnsley, Doncaster, Wakefield etc.

As an aside, the integrated settlements given to mayoral authorities are meant to be about giving places control so they can deliver better outcomes for their area. Tools of central control like the business case requirement for transport projects worth over £200m - or the idea of very specific outcomes frameworks - is not supporting this key aim.

100%! Where I live in Germany has a population of 130 000, with a fully integrated mass transit system including reliable trams, buses and regional trains. At the recent mayoral election here it was seen as a disgrace that one of the tram routes did not extend to one of the small nearby neighbourhoods.

The fact that so much of northern England lacks this infrastructure (the population of Leeds is at least 6 times this German city!) is a disgrace and is withholding the north’s potential!

Touring Huddersfield station yesterday I was struck by two things: the simplicity and beauty of the planned overhaul (it is really exciting to hear about the fully developed plan); in contrast though the suggested timescales to completion were a little dispiriting. Walked away thinking I won’t be able to catch a train from Huddersfield to Bradford for over a year from now (without the aid of bus replacement via Brighouse). We should be able to do better. Understand line upgrade et al but it has taken so long already.