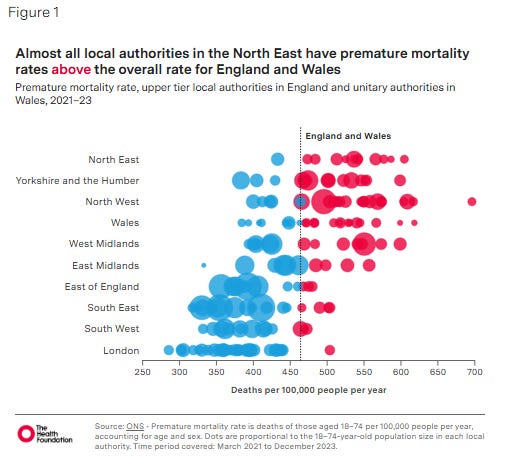

For a boy born in Blackpool, life expectancy is ten years lower than for one born in Hart, Hampshire.1 And as the chart below shows, local authorities in the North have higher premature mortality than the average region.

Source: Health Foundation - clickable graphic available

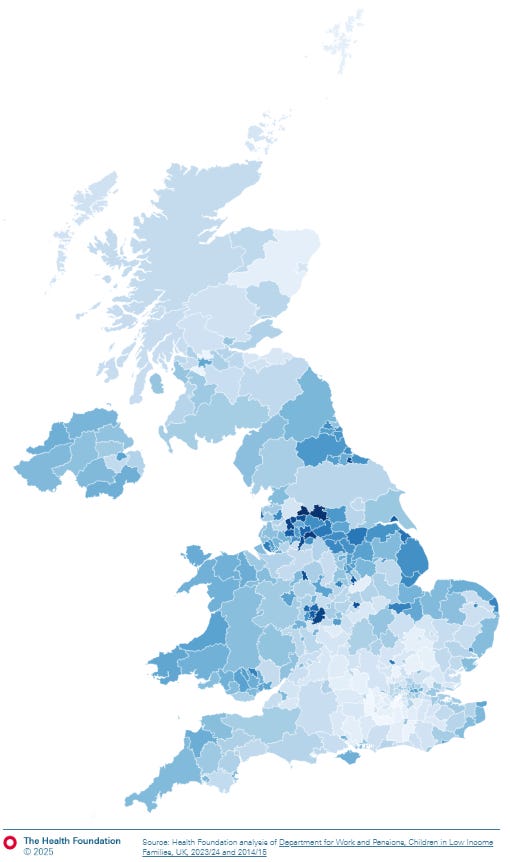

Child poverty rates have also been stubbornly persistent. And it is highest in urban parts of the North (darker colours in map below). 2

Source: Health Foundation - clickable map available

Fixing these issues for the long term is not simple, but it is good to see action starting to be taken.

The NHS ten year plan wants to shift the focus of health to neighbourhood services starting with 43 areas and the government has also said that there will be a child poverty strategy published this year. The extension of free school meals to any child on universal credit - alongside free breakfast clubs in primary schools - is a clear indication of their ambition, though the debate on the ‘two child’ rule will inevitably be the framing for whatever emerges.

But here in the North, mayors and local authorities have not been waiting for central solutions or permission to make progress on tackling issues like child poverty.

In 2024, the Mayor of South Yorkshire - Oliver Coppard - started a ‘beds for babies’ scheme using £2m to ensure all under fives have a safe space to sleep after referral by local organisations.

And in 2025, the Mayor of the North East - Kim McGuinness - approved almost £29m to fund a North East Child Poverty Action Plan including pilots for pregnancy grants, baby boxes and increased youth activities. Indeed the mayor said that it is her ‘number one priority’.3

Both of these developments are very exciting because they show that mayors and strategic authorities are doing things differently in their areas. Some would say that this is beyond their ‘remit’ as they should focus on economic policy and growth. But, I think that this is wrong for two reasons.

Firstly, reducing poverty and helping children and families in the ways described above, is not just intrinsically good, but also clearly good for the economy. Sickness, poverty and a lack of local services are not helping children trying to learn, or people trying to find work or sustain a job.

For example, Health Equity North looked into the links between the decline of high streets and health inequality. Vape shops are twice as prevalent in the North, whilst supermarkets and departments store numbers have declined more than in the rest of the country. IPPR North recently looked at the experience of young people. Library closures have been highest across the North due to local government cuts.

Secondly, the argument that mayors were created to focus solely on economic policy is ahistoric. Mayors are increasingly responsible for police and crime in their areas, with the Mayor of London having had this power since 2012. And even the Coalition government piloted health and social care devolution with Greater Manchester in 2014. The 2024 Devolution White Paper also gives mayors a role in public service reform and appointing the chairs of Integrated Health Boards.

The key benefit of these reforms is that they allow policies to be tailored to places, so that we can see what works - and what does not - in a way that it is difficult to do when everything is controlled centrally. As places learn, they can then improve their policies over time to help support children and families in the right way.

Interestingly, a recent evaluation by the Blavatnik School of Government at Oxford supports the idea that more localised ways of working can improve people’s lives. Though the ‘Kirklees Better Outcomes Partnership’ (KBOP) was not focused on child poverty, it is a vote of confidence in these kinds of public service reforms.

KBOP has operated since 2019 to develop a more outcomes based approach to delivering support services for people at risk of homelessness. 4

What this means in practice is that Kirklees Council pay for positive outcomes (e.g. prevention of homelessness), rather than service providers being paid a grant based on expected caseload under the previous model. This quote from the evaluation explains in basic terms how the new service worked.

“A central innovation introduced by KBOP was its shift to a person-centred model of housing-related support … tailoring support to the individual’s strengths, preferences, and priorities rather than focusing on deficits or standardised risk profiles.”

Basically, the central KBOP hub was able to triage people and then point them to the right local services in line with the process described above. This is simply not something you can do from central government.

The impact of this has been found to lead to statistically significant increases in employment in the months and years afterwards. There was also a statistically significant reduction in benefits paid as a result. The report says that KBOP ‘delivered improved outcomes at a lower marginal cost compared to the traditional fee-for-service approach.’

It is great that local authorities like Kirklees are innovating and improving their services like this. The change needed, on the scale required, is going to require both national and local governments to step up to deal with inequalities in life expectancy and child poverty.

So whilst there are significant challenges in terms of health and poverty across the North, different institutions and organisations are working to improve people’s lives. More work is clearly needed. But, it is brilliant to see evidence based local initiative thriving, tackling some of our biggest social ills.

Child poverty here is defined as when a person under 16 lives in a household with a net income below 60% of the median income. The definition used in the above map for the Health Foundation doesn’t account for housing costs (drawing on the DWP data here). If you look at child poverty rates after housing costs, then London does comparatively worse. See this JRF analysis for a fuller discussion with a regional breakdown taking housing costs into consideration. In the 2023 JRF figures, the West Midlands has the highest rate of child poverty after housing costs (27%), followed by the North West (25%) and London (24%). The lowest is in the East (18%)

Interestingly, this £29m of funding from now to 29/30 is funded from the ‘North East CA Investment Fund’ according to the CA papers. I think this is comprised of the annual grant received from the government when new mayors are created (and potentially from the integrated settlement when that is confirmed). See agenda detail here. This annual grant funding is often known as ‘gainshare’ as its origins lie in giving areas some of the upside that devolved power is meant to bring in terms of growth (in the absence of fiscal devolution all fiscal upside otherwise flows to central government). That the North East Combined Authority - comprised of Labour, Conservative and Reform members - has decided to prioritise child poverty with this funding shows that the seven local leaders there understand the importance of tackling poverty to other goals like growing the economy. You can watch the approval of the plan on a cross-party basis here.

Until 2024, 30% of the funding was provided by central government - but Kirklees has chosen to retain the model after the funding ended (but scaled down given the reduction in grant). This is also a good point to add that I happen to live in Kirklees.

In an age when economic trends favour agglomeration of services for cost and perceived organisational benefits (health trusts, school trusts, legal services, children’s service et al) this article presents a really timely and apposite counter argument. So true JP; many fields of Public Policy really are better deliverred to local people by local groups responding to particular circumstances.